Photos and objects

NB: Click to see the entire photos.

Educating the people I

The Kristiania working men’s institute was founded in 1885 with the aim to disseminate useful knowledge and offer new cultural experiences. During the first 25 years since its establishment, the institute held 5,826 lectures with about 888,000 attendees.

These glass slides come from the lectures on human evolution and racial research by the military doctor Carl O.E. Arbo (1837–1906).

Photo: C.O.E. Arbo / The Norwegian Musuem of Science and Technology.

Educating the people II

The Kristiania working men’s institute was founded in 1885 with the aim to disseminate useful knowledge and offer new cultural experiences. During the first 25 years since its establishment, the institute held 5,826 lectures with about 888,000 attendees.

These glass slides come from the lectures on human evolution and racial research by the military doctor Hans Daae (1865-1926).

Photo: Hans Daae / The Norwegian Musuem of Science and Technology.

Blumenbach's system

German anatomist and professor of med- icine Johann F. Blumenbach (1752–1840) offered one of the first descriptions of generic human types by expanding the biological classification system of Swedish botanist Carl von Linné (Systemae Naturae, 1735).

In 1795, Blumenbach concluded a system that connected geographical origins with mor- phological appearance. He attributed these variations mainly to climate and argued that all humans belonged to the same species. But to him, the most beautiful people were those who came from the Caucasus Mountains, or the “Caucasian race,” which he portrayed as the original human type.

Photo: Håkon Bergseth, NTM / Oslo Cathedral school old library.

“Mr Bullock’s exhibition of Laplanders”

In 1821, a British collector, William Bullock, hired a Sami family to care for a small rein- deer herd he brought with him to London. In 1822, he exhibited the family along with the animals and cultural objects in his museum, the Egyptian Hall. Bullock was an ingenious entrepreneur who advertised the exhibit extensively using press ads and media stunts.

More than fifty-eight thousand people visited it during the first few months after the opening; it later toured Ireland and Scotland. The press described it as both entertaining and educational.

Photo: Thomas Rowlandson, "Mr Bullock's Laplander exhibition" / National Library of Norway.

Phrenological “national” skull

Phrenology, with its emphasis on classifying skull shapes and on the connections between biological and character traits, was a precursor to physical anthropology. Although later seen as a pseudo-science, it enjoyed high prestige among early anthropologists.

This skull was part of a series of 33 casts sold in Stockholm by the Institute of Technology in 1834–35. The founder and leader of the institute, Magnus Gustav Schwartz (1783–1858), was one of the main Swedish phrenologists.

Photo: Håkon Bergseth, NTM / University of Oslo: Institute for Basic Medical Sciences.

Von Luschan's chromatic scale

The thirty-six standardized opaque glass tiles in this scale represented shades of skin color and, along with other physical characteris- tics, were used for racial classification. The method relied on simple visual skin-color matching by comparing areas of skin (ide- ally not exposed to the sun) to the color of the tiles. Its inventor was the Austrian-born anthropologist Felix von Luschan (1854– 1924).

Although criticized as subjective and imprecise, the scale was used interna- tionally from 1900 until the mid-twentieth century. By the 1950s, reflectance spectro- photometry had replaced it in anthropological research.

Photo: Håkon Bergseth, NTM / University of Oslo: Institute for Basic Medical Sciences.

Occipital goniometer

This instrument was used for measuring skulls to determine the angles of the back of the head. It was invented by French anatomist Paul Broca (1824–1880), the most influential physical anthropologist of the 1860s and ’70s.

The Norwegian pioneer Carl O. E. Arbo was one of many who traveled to Paris to learn this subject in the 1870s.

The instrument was produced by the firm of R. & H. Mathieu in Paris in collaboration with Broca.

Photo: Håkon Bergseth, NTM / University of Oslo: Institute for Basic Medical Sciences.

Alette and Kristian Schreiner: Partners in science and in marriage

Kristian (1874–1957) and Alette (1873–1951) Schreiners’ joint microscopic studies of cells contributed to great breakthroughs in chromo- somal research and genetics at the turn of the twentieth century.

Kristian’s appointment as Professor of Anatomy at the University of Oslo in 1908 triggered the married couple’s strong commitment to physical anthropology.

Alette concentrated on the physical characteristics of the living Norwegian population. The com- parison between living and past populations was intended to show which racial types had lived in Norway in the past and given rise to the Norwegian and Sami people.

Photo: Unknown photographer / University of Oslo: Museum of Cultural History, Section for Museum of University and Science History.

Halfdan Bryn: The foremost anthropologist in 1920s Norway

The military doctor Halfdan Bryn (1864–1933) was one of Norway’s leading anthropologists and most respected scientists during the 1920s.

In 1920–21, Halfdan Bryn initiated a major survey of recruits in collaboration with Kristian Schreiner. This atlas, the main product of the survey, reached no overarching conclusion. It took many years to analyze the enormous amounts of data collected and along the way, the authors disagreed on how to interpret the findings. This was an ideologically charged conflict.

The Schreiners distanced themselves from Bryn as he became increasingly invested in extreme notions of racial superiority. Photo: Jens Carl Frederik Hilfling-Rasmussen / NTNU UB.

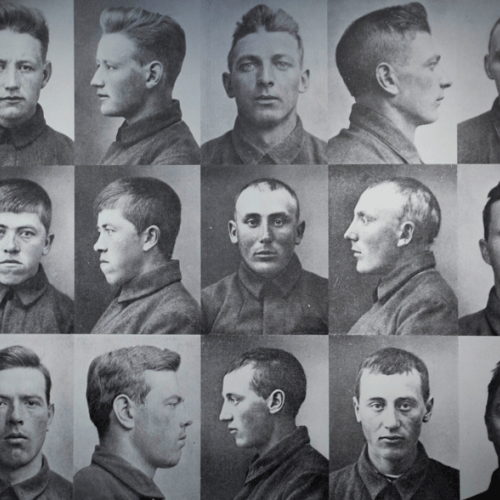

The large-scale survey of recruits

All young Norwegian men who did military service in 1920–21 underwent physical-anthropological measurements of body type, head shape, eye color and hair color. Many were photographed.

Recruits were popular research subjects in many countries. They were readily available, and were considered a representative sample of a nation’s population. Recruit photos and measurements were used to divide the national population into racial types, and were published internationally.

The race survey participated in a transnational science that sought to divide humanity into racial types and explore their evolutionary history.

Photo: Åsa Marie Mikkelsen, NTM / Halfdan Bryn and Kristian Emil Schreiner in Bryn & Schreiner, Die Somatologie der Norwege nach Untersuchungen an Rekruten. Oslo i kommisjon hos Dybwad, 1929.

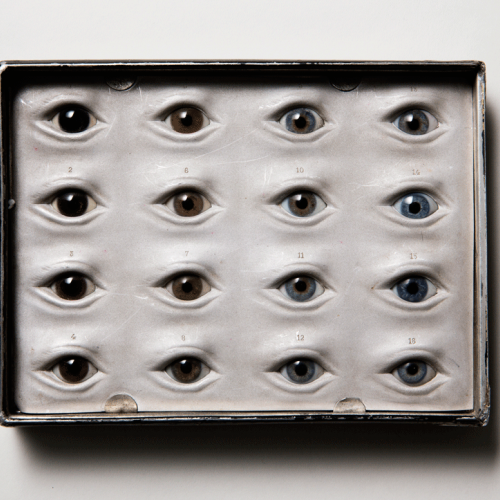

Martin’s eye color chart

This eye color chart was developed by the influential anthropologist Rudolf Martin (1864–1925).

In spite of standardized methods of description, eye colors do not tend to fall into natural racial types. The scientists conducting the Norwegian race survey fundamentally disagreed about how best to categorize the eye colors of their Norwegian subjects.

Photo: Håkon Bergseth, NTM / University of Oslo: Institute for Basic Medical Sciences.

Eugen Fischer’s hair-color scale

Hair color was classified with the help of this internationally standardized instrument developed by the influential German geneti- cist and anthropologist Eugen Fischer (1874– 1967).

owever, as with eye color, hair color comes in many shades and cannot be placed into naturally given categories. For example, where is the boundary between blond and light-blond hair, and what degree of blond- ness characterized the Nordic race? Such questions created conflicts when it came to analyzing data collected in race surveys in Norway and elsewhere.

Photo: Håkon Bergseth, NTM / University of Oslo: Institute for Basic Medical Sciences

To Tysfjord to study the “Lappish” racial type

The recruit survey was part of a larger national project that included surveys in several local communities. Anthropologists Alette and Kristian Schreiner conducted a local study at Hellemo in Tysfjord in 1921. Kristian Schreiner had also visited Hellemo in 1914, assuming it had a relatively unmixed Sami population.

By comparison with contemporary populations elsewhere and with human remains from past populations, the Schreiners attempted to iden- tify an assumed “Lappish” racial element and highlight the origin, migration, and settlement of this racial type in Norway.

Their purpose was not to rank people hierarchically by race. But the Schreiners’ perception of the Sami as racially primitive affected their research and their encounter with the locals.

Above: Portait of Inger Nikolaisdatter Tjikkom (b. 1879), with her children Sara and Peder. She was widowed in 1914. The photo was taken in 1914 by doctor Johan Brun, Schreiner’s associate during the survey.

Photo: Johan Brun / University of Tromsø: Tromsø museum and Árran Lulesami Center.

To Setesdal to study the “Nordic” racial type

Valle in Setesdal played a significant role in the large-scale race survey of Norway. Based on previous anthropological studies in that place, researchers expected to find a nearly pure Nordic racial type in the population.

The race survey only included measurable physical characteristics, but the research was influenced by ideas about the Nordic race’s assumed psychological characteristics.

Alette Schreiner identified Torleif Aakre as a prototypical Viking, and described him as intelligent, vital, poetic, healthy, and handsome.

Above: Portrait of Torleiv Bjugsson Aakre (1880–1972). He got married to Gyro Bjørnsdatter Harstad (1880–1929) in 1908 and had four children. Torleiv was interested in history and wrote articles about Setesdal in the press.

Photo: Kristian Emil Schreiner / University of Oslo: Institute for Basic Medical Sciences and Norsk Folkemuseum.

Race hygiene/eugenics

Race hygiene or eugenics was an international movement with a major impact in scientific circles.

Eugenicists feared for the future. They believed modern society kept people alive who otherwise would have lost the struggle for existence. They therefore sought to reduce births among “inferior individuals.”

People were judged according to their hered- itary characteristics. This was not neces- sarily linked to ideas about racial difference. However, many eugenicists in the United States, Germany, and Scandinavia aimed to protect the “Nordic race” against race-mixing and to help it grow at the expense of “inferior” races.

This is a eugenics propaganda poster from the UK (ca 1935). Click to see the whole poster.

Photo: Galton Institute/Eugenics Society Archives, Wellcome Institute Library.

Jon Alfred Mjøen, racial hygienist

In the interwar period, Jon Alfred Mjøen (1860–1939 was the foremost Norwegian spokesman for racial hygiene. In 1906 he founded Vinderen Biological Laboratory, where he researched topics including the genetics of musicality and criminality.

He supported the idea of the existence of a Nordic racial elite and argued that racial mixing could lead to hereditary inferiority. He built his arguments partly on his studies of rabbit heredity and of what he considered race-mixing between the “Lappish” and “Nordic” races.

Mjøen was an internationally known racial hygienist with many supporters and opponents within the eugenics movement. Halfdan Bryn supported Mjøen’s view of race-mixing. Kristian Schreiner was dismissive.

These slides come from one of his lectures on eugenics.

Unknown photographer, Jon Alfred Mjøen / NTM.

Nazism and race science

At the center of Nazism stood the idea of a racially superior Nordic-Germanic people that had the right to expand at the cost of other races. Together with an intense hatred of Jewish people, this concept was a funda- mental motivation for the Nazi genocide.

But this way of thinking did not emerge in a vac- uum. The Nazis built on ideas that had long been in circulation across national boundar- ies and were well represented in scientific discussions. The German academics involved in shaping the Nazis’ racial policies worked in close collaboration with fellow thinkers in other countries.

When the Nazis took power in 1933, they were met with strong opposition from the scientific community, but found sup- port from scientists who were willing to place their skills and knowledge in the service of the new regime.

Scandinavia was considered the cradle of the so-called Nordic-Germanic race, while Norwegian racial anthropology was diligently quoted in Nazi propaganda literature. In this photo from 1945, we see Jewish children who survived Auschwitz.

Photo: Unknown photographer/United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Belarusian State Archive of Documentary Film and Photography.

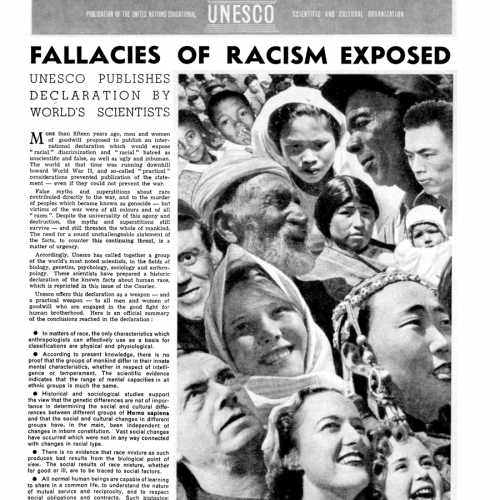

Anti-racism in science and society

Racial discrimination around the world, and accumulating scientific evidence, prompted scientists, activists, and politicians to speak out against racism. Starting in the 1950s, UNESCO began issuing formal statements on race. These became a symbol for postwar anti-racism.

The Statements pointed to popular misunderstandings and political abuses of the concept of race. They also introduced a new way of regarding races as populations with differing gene frequencies. The authors were leading science experts in the relevant fields. Despite diverging opinions, they all agreed that humans belonged to the same species, Homo sapiens, and that human groups did not differ in their innate capacities for intellectual and cultural development.

Many biologists continued to study races defined as genetically distinct populations. At the same time, these Statements contributed to an under- standing that racial categories were not to be found in nature but were instead products of cultural and social conventions, and therefore open to change.

Photo: UNESCO Courier July-August 1950 / UNESCO.

International anti-racism

In 1948, the United Nations General Assembly adopted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights as a reaction to the atrocities of pre- vious world wars. The same year, the South African government introduced apartheid. UNESCO’s anti-racist campaign targeted Nazi racial science, but avoided the contentious issue of continued segregation in the United States. In the US, however, opposition to racial discrimination was growing; in the 1960s, parts of this movement joined forces with the peace movement and the new wave of fem- inism. In 1964 and 1965, the Civil Rights Act banned all discrimination and segregation in public, and the Voting Rights Act aimed at ensuring that African Americans could exercise their voting rights. Apartheid in South Africa officially came to an end in the early 1990s.

In the photo, Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X are waiting for a press conference on 26 March, 1964.

Photo: Marion S. Trikosko / United States Library of Congress's Prints and Photographs division.

Race to the genome

Designing and developing cheaper and faster DNA-sequencing technologies was one of the primary objectives behind the Human Genome Project as it emerged in the early 1990s. The overall aim was to complete mapping of the human genome and identify all of the genes it contains.

An international consortium of more than two thousand scientists from twenty labs and three continents was established. In February 2001, the covers of the journals Nature and Science featured the news of the draft human genome sequences produced by the International Human Genome Sequencing Consortium and the private company Celera Genomics.

By April 2003, the group had succeeded in sequencing ninety-nine percent of the human genome. The biomedical applications of the project for individuals and society were heav- ily emphasized throughout, and critics raised concerns related to the overall genetic hype and the emphasis on genetic explanations.

They also pointed to possible genetic privacy breaches, discrimination, and patenting, as well as to the extremely high cost of the project.

Photo: Håkon Bergseth / NTM.

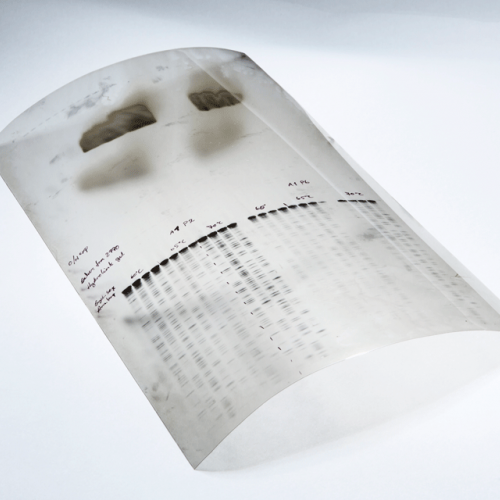

Reading DNA sequences

The biochemist Fred Sanger (1918–2013) and his col- leagues developed a new technique to determine the order of bases in DNA fragments in 1975. Radioautography was used to visualize it.

By the end of the 1970s, they had been able to sequence the genome of a simple organism. The Human Genome Project used Sanger’s methods to deter- mine and assemble the sequences from many small frag- ments of human DNA.

Photo: Håkon Bergseth / NTM.

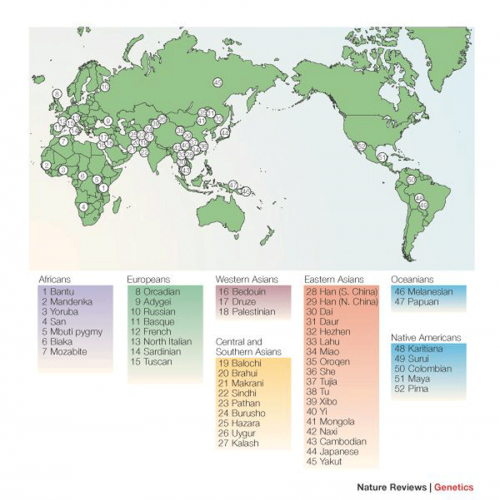

Human Genome Diversity Project (HGDP)

The Human Genome Diversity Project launched in 1991 with the aim of illuminating how human- ity spread from its origins in Africa and pop- ulated the globe. The project collected blood samples with a specific focus on indigenous peoples, whom the researchers perceived as long isolated and about to die out.

The project generated scientific controversy over its ethi- cal, methodological, and theoretical premises. Several anthropologists argued that the very idea of genetically isolated indigenous peo- ples was an empirically unjustified holdover from the racial ideas of the colonialist era. By systematically looking for genetic differences between culturally defined groups, critics argued, the project could ultimately provide support for racial prejudices.

In 1993, the World Congress of Indigenous Peoples labeled it the “Vampire Project”. Indigenous groups worldwide demanded the project be halted on the grounds of disregard for their world- views, possible patenting and exploitation of their genomic material, and lack of informed consent.

Photo: Luigi Luca Cavalli-Sforza, (2005). "The Human Genome Diversity Project: past, present and future", Nature Reviews Genetics 6, 333-340.

From skulls to faces

This facial depiction is based on the remains of a Viking Age woman found in a typical Norse burial in Nord-Trøndelag, Norway, in 1927. When she was first described anthropologically, Kristian Schreiner categorized her cranium as being of “Nordic” type.

In 2015, DNA analysis showed a maternal lineage rare in Europe but common in Turkish populations and the Black Sea region. In 2017, DNA from the same skull was used for research on Viking migrations at the Centre for GeoGenetics in Copenhagen.

In 2018, Face Lab combined DNA results for hair and eye color with archaeological and biological-anthropo- logical / anatomical data to produce the facial depiction. The long journey of this skull points to changes and continuities in classifications and practices of research, and raises questions about what we can learn from human remains.

Photo: Face Lab, Liverpool John Moores University, UK / NTM.

Unearthing Sami remains

In July 1915, doctor Johan Brun arrived at the Sami area of Neiden, in Finnmark, Norway. Kristian Schreiner had commissioned him to excavate skeletons from closed cemeteries with permission from the Norwegian authorities.

Brun set up camp outside the Russian Orthodox chapel, but the locals protested the exhumation of graves around the site. As Brun reported, he excavated in adjacent land after negotiations with a local landowner and uncov- ered a supposedly older burial ground. The skeletons were transferred to the University of Oslo.

Brun’s visit to Neiden was part of a larger endeavor to collect skeletal material from Sami burials for physical anthropological research. In 1999, the university acknowledged that the collecting had taken place unethically and transferred administrative control over all Sami remains to the Sami Parliament.

In 2011, the remains of ninety-four people were reburied in Neiden, Norway.

Photo: University of Tromsø: Tromsø museum and Árran Lulesami Center/Johan Brun.